There are things publishers can’t count on the internet. Things that don’t show up in Google Analytics or in Chartbeat.

I know that sounds like heresy in the age of pageview quotas and dashboard fetishism.

It sounds a bit odd to say, like a vote of no confidence, coming from a co-founder and CEO of a data-driven engagement company – Contextly. I know firsthand some of the incredible things that can be built using data and algorithms. We innovate publisher engagement tools like our FollowUp button. It is, however, important to know the limitations of your tools.

And the uncountable things are very important things.

They may, in fact, be some of the most important things to publishers.

Things like a publisher’s reputation. Or, as some call it these days, their brand.

Here’s a few things that publishers can’t and don’t count:

- Do “content recommendations” on the site appeal to readers’ basest selves and make readers feel dirty for clicking them?

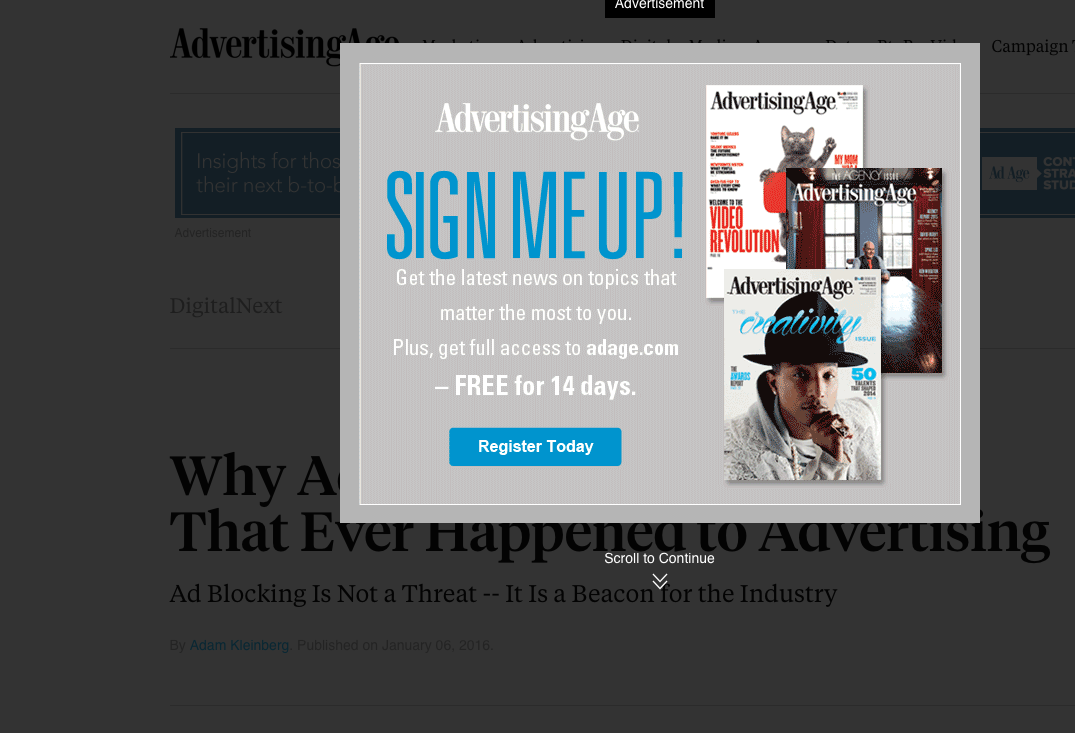

- Do readers start reading a story only to have that story blocked by a pop-up with X that’s nearly invisible to find or requires them to click on a link like “No, I don’t want to buy life insurance to protect my family. Let them beg on the streets and build character.”

- How do readers feel about having to be the Lloyd Bridges in Airplane fighting off petitioners as he enters the airport — when all the readers want to do is just read to the end of an article?

- Do the ads insult their intelligence?

- How many times do readers sigh? Or curse?

- Do low-quality recommendations on the site pretend that they are personalized, even for readers that have never visited the site before?

- Is the site readable on mobile devices?

- Did a new-to-your-publication reader who followed a story link even remember the name of your site – or did they read one story and bounce off?

- Are you covering the issues and stories that your core community cares about?

The Rise of Ad-Blockers

There are some ways to measure this now, obliquely: Bounce rate, for one.

But there’s a better indicator: count the number of readers who are using ad-blockers.

Certainly, there are some readers who simply hate all ads on principle. There are those who equate any tracking, however benign and pseudonymous, on par with the NSA’s warrantless wiretapping.

But the majority of readers who are adopting adblockers seem to be doing so because the publishing industry has all too often made reading on the open web an awful experience.

Though there’s been much written about the number of trackers and the size of pages loading, I strongly suspect that most people who turn to adblockers have no idea how many trackers run on publishers pages. They may notice a site that is slow to load, but I doubt they are actually measuring the size of a page.

Instead, ad-blockers are – by and large – readers fighting back against being insulted.

Tragedy of the commons economics underpins this race to the bottom. Publishers increasingly over-harvest a resource that is a pillar of their existence – reader attention and trust. Publishers have failed to implement the collective discipline required to conserve this valuable resource so that future generations of editors, writers, and readers can benefit from it.

Instead, they compete to liquidate as much of this resource as they can because, if they don’t, another publisher will.

But intriguingly, the digital winners aren’t doing this. Medium has carved out a niche with a supremely clean reading experience. The New York Times and the Washington Post have stayed far away from the tricks and gimmicks, growing both their audience and reputation. Vice has stayed clean too. Skift, Rafat Ali’s travel vertical, is also quite smart.

But how many times have you visited a site for the first time, only to have the story you are reading blocked by a pop-up imploring you to follow the publisher on Facebook or subscribe to an email – before you’ve even finished a single story?

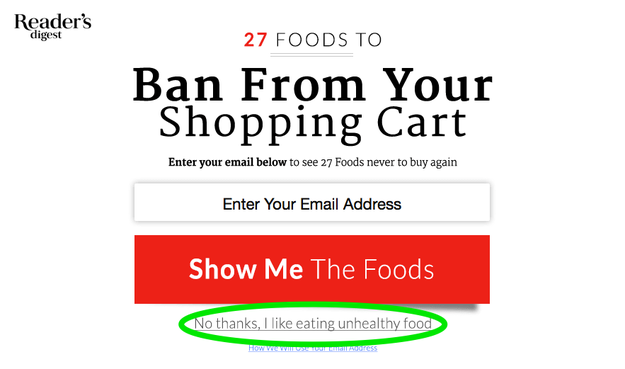

And how many of those pop-ups put the close button in a non-obvious place – or make you click a link like “No, I don’t want to be smarter by subscribing to your email list.”?

Lydia Laurenson, a friend of mine, even got a bit of internet fame posting snapshots of these pop-overs on a Tumblr called Cruelest Opt-Outs (and, no, I didn’t know she did this until I read a story about it).

How about, in the midst of reading a story, an auto-playing video ad starts with the audio turned? Thanks for making me look like a jerk in the cafe.

Next you might get an obnoxious flyout slider coming in from the bottom right corner, pulling your attention just as you are about to finish an article. The movement plays on your flight-or-fight response, and at least for me, invokes just anger.

Readers should get points or badges for killing off these annoyances.

And then, at the end of the story, there are “recommended stories” that are often unlabeled ads trying to entice you to the lurid diet-pill shakedown neighborhood of the web.

Each of those annoyances do get clicked on by some percentage of readers, even if that percentage keeps decreasing over time as readers catch on.

Publishers can see those clicks in their analytics. Someone somewhere in the publication is looking at those clicks and calculating a bonus trip to Cancun.

But there’s no section in Google Analytics that registers reader disgust.

Nobody gets a bonus for making readers happy on the site. There is no metric for it.

They should.

It’s not just gut instinct that says site experience and reader trust matters. A new study by the Media Insight Project found that only 12% of readers trust what they see on Facebook and the decision to click is about whether they trust the publisher of that story. And readers that trust a site are more likely to share stories, download apps and pay to subscribe.

But you can’t measure trust in Chartbeat or Google Analytics.

For instance, this weekend I saw a link on Twitter to a story analyzing why the Golden State Warriors’ players Stephen Curry and Draymond Green were so dominant. The story was on was on Warriors World, a Golden State Warriors-focussed site I’d never heard of before (and I live in Oakland so I’m a prime candidate to be won over).

I got to the end of the article, thinking I’d read more from this site, but the “content recommendations” at the bottom were low-grade traffic arbitrage from RevContent.

I bounced. And I doubt I’ll be back. Certainly not on purpose.

And as I was writing this, I had to put “TKTK” in as a placeholder for the name of the site. I literally didn’t remember the name of the site, and had to go back to my phone to put the right name in this piece. I all remembered was it was “warriors-something.”

So what’s to be done?

One idea is that a publisher needs to have a Reader Advocate – like a public editor or ombudsman but for experience. Something like what software companies do when they hire Developer Advocates whose job it is to nurture and fight for the outside developers who usee the companies’ APIs.

Of course, it’s even better is to NOT need a reader advocate.

That means that the organization’s culture thinks from a reader’s perspective; from the publisher through the editor-in-chief to the ad sales team to the marketing team to the social team to section editors to the writers to the dev team. Anyone in that chain should be free to speak up and say, “This feature sucks for readers” or “This ad campaign should never have been allowed.”

This happened once, years ago, when I was at Wired (not saying Wired was perfect). The ad team sold a big corporation on sponsored posts that would be written by the company. Every section was going to get at least one and the company didn’t want the posts called out in any special way. No Sponsored label, no different color; just bylines that indicated they were written by that company’s employees.

The Wired editorial team mutinied. There was a coalition of editors ready to quit over it; confronting management. We eventually got to a compromise (and the posts were labeled) and, we got a promise that no such campaign would ever be sold again without the advertiser knowing the posts would be labeled.

But, honestly, that’s a last resort. The editorial team shouldn’t ever have to think about that. There should be someone appointed as Reader Advocate – or if more palatable, Brand Advocate, who steps in to stop short-sighted decision making that cares about short-term metrics at the expense of reader experience.

Sites also need to *listen* for the site’s community talking back.

Readers are used to ads. They are even used to ads in media that they *pay* for; from ads in magazines to cable channels full of ads to old-fashioned newspapers.

Readers don’t even mind ads that aren’t useful to them personally, so long as the ads don’t suck. I saw a sidebar ad today on a local news site advertising a gun show. I’m not a gun owner or enthusiast, but I didn’t mind the ad at all. We’re used to filtering out ads that don’t appeal to our interests, without being angry about it.

Take this comment on a thread on Hacker News about ad tech.

The thing about ads is, if they are done right, they are very useful. For example, I buy hot rod magazines specifically to get the ads (the articles are the fluff). I enjoy the previews of coming attractions when I watch a movie, and use them to decide what to watch. I enjoy watching “Detroit Muscle” shows on TV because they are about product placement (they show how to use the products to work on your car.) Etc.

Making money off online content, especially in the age of mobile, is not a simple problem; but the first step of fixing a problem is acknowledging it.

Here’s how Adam Kleinberg put it in a post about adtech and ad blocker for AdAge:

Many see ad blockers as an existential threat to our business. I see them as a beacon. This is collective intelligence at work. This will be how the Wild West is won. The industry hasn’t been able to police ourselves, so consumers will force change upon the industry themselves.

Advertising doesn’t have to suck. We can tell great stories with digital. We can create marketing that provides value to consumers instead of hurting them. We can even leverage data to do it in an increasingly relevant and efficient way.

If consumers have anything to say about it, we’ll have to.

There’s no single silver bullet for publishers.

Getting readers great experiences requires lots of lead bullets: Stories readers care about; good headlines; smart images; readable fonts; great recommendations; ways for readers to find the information they need; a real voice on social channels; fast loading pages; effective, but not insulting, ads.

But it’s not too late for publishers that have identifiable audiences and communities.

Publishers can rebuild. They just have to wean themselves off the income of slowing selling off the value of their brands.

They have to start stop valuing metrics that ignore the impact of awful reader experiences, and start caring about how they treat their community.